No one's brought up politics for a good long while on these here pages, and so I thought a decent approach to this election season would be to draw everyone's attention to two things; one is a humourous anecdote about one of my favorite songwriters, and the other is something our good friend Nick Smerkanich pointed out to me.

First and foremost I'd like to start with a brief plea. To concert goers everywhere: stop being such a bunch of mean, noisy fuckheads. You people seem to come to concerts simply to muscle your way to the front and then spit beer at people. You don't care about anyone but yourselves, you're rude, you smell horrible, and everyone who likes music hates you. Get a fucking clue and never go outside again unless you can handle it. Humanity is innate, and so being around people isn't a right, it's a privilege. If you can't understand that you're hulking frames and unfathomable ignorance make people uncomfortable, including but not limited to the band, you don't deserve to be out among people.

I've seen Spencer Krug in concert twice in as many months. First with his collaborative project Wolf Parade, then with his own songwriting vessel Sunset Rubdown. Both times the seriously inconsiderate behavior of concert goers have made him too uncomfortable for words. At the Wolf Parade show, a group of Philadelphia-area yahoos rushed the front row and started slam dancing and pummeling each other and strangers. At first guitarist/vocalist Dan Broeckner and Krug, the keyboard player and one half of the vocals took a calm approach. "I don't mean to get all Ian McKay on you guys, but you should love each other", came Broeckner's mellow warning. Krug too uttered non-threatening advice a few times until the encore came about. When the reprehensible behavior of the boys in the frontrow would not let up, Krug looked at them from the corner of his eye and spat with as much seething contempt as could fit in his words "I don't know why you have to fucking hit each other." Being Canadians, I have to guess they aren't used to American views on concert going. I sympathize with Krug and his bandmates and I apologize on behalf of the rest of us; those who feel embarrassed to share concerts with these people.

The next time I saw Krug, he was clearly worn down by America. Tired, irritable, and a little red in the face, his Sunset Rubdown delivered a stellar performance. The energy and passion was there and I can't help but feel it was Krug's claustrophobic reaction to America that made him perform so well. This time the drunks were not in as full force as before, but that didn't stop a scene from breaking out. About 3/4 of the way into their set, a large man and his large girlfriend, beer in hand, waltz to the front row and begin making everyone uncomfortable with their obnoxious dancing and drunken logic. During songs they would shout and swear and dance and make out, "sometimes you just gotta dance." Krug made to apologize for his set starting later than anticipated when his animosity was provoked; Hyde stepped out.

"I'm sorry we took so long, guys."

"I'm sorry no one's dancing. I'm going to fix that!"

"That's not your responsibility."

Now, I go to concerts for moments like the wordless verse after the first chorus of

'Shine a Light' that I witnessed at the Electric Factory. That moment was for me the reason to see live music, when the band is so in tune with each other, and the groove so solid and undeniable that one has little choice but to bask in the power of music. This was a perfect 15 or so seconds in an evening filled with truly awesome performance. I go to experience moments of true artistic transcendence and to share these precious moments with like-minded individuals and close friends. Why, then, do drunken barbarians go to concerts? I cringe everytime I think about the fact that nothing will change the fact that I'm an American and so are all these fuckheads. Sorry for all the profanity, but understand that i don't take this lightly.

The real reason I bring up this Sunset Rubdown song is to illustrate that clearly everyone has an interest in how our election turns out.

Not quite verbatim Krug quotes from Sunset Rubdown's show at the Middle East in Cambridge:

"The name of that song is 'Don't elect Sarah Palin'"

"The real title of that song is 'Please don't elect Sarah Palin'"

"The long title of that, as it appeared originally was 'I don't neccesarily agree with all of Barack Obama's policies, but I'd vote for him just so that Sarah Palin doesn't get elected'"

Even Canadians hate American Republicans. I hope the first time John Johnson leaves the country, he has to explain to a group of Afghan refuges why America blew the shit out of their country and killed their relatives. I'm not taking this lightly. Party affiliation is one thing, but guess what doesn't mean shit if you don't have personal politics that extend beyond intangible concepts like 'the economy' and 'patriotism'.

Part 2 of this litany of liberal screaming:

It's no small secret that I'm an enormous fan of the critically acclaimed television series The West Wing. It's combination of perfect aesthetics and brilliant political dialogue were unrivaled during it's run, and Aaron Sorkin's writing was so forward-thinking and furious during a time when nightmares guided news cycles and wars were being fought on our behalf (oh, wait, nothing's changed). So here is a piece of Sorkin's writing, his two cents on the upcoming election. It is a trifle silly, but if you've been paying attention, we seem to all be living in a particularly frightening room of Willy Wonka's chocolate factory, so I find it comforting that Sorkin has taken the low road, as it were.

Here Sorkin reaches a hand into his bag of tricks and removes one final liberal cry of hope

If you're out there, are over 18 and think for a second that your vote doesn't matter, or worse that voting for Barack Obama is the same as voting for Mccain, you're wrong. This time, you're dead wrong. Please don't let Fascists win. Not again. I'm so tired of living in a Philip K. Dick novel.

Note

In mentioning the films with my favorite examples of cinematography, I realize now I forgot to mention my favorite technicolor film of all time (in photographic terms. All That Heaven Allows might be a better movie, but Korda's Thief of Bagdad is just so majestic).

Directed in part by (small wonder) Michael Powell, master of outlandish colour schemes and pointy facial features, this film is one cinema's great fairy tales (from a time when they could still be done innocently and beautifully a la La Belle et la Bete and les Enfants du Paradis). George Perinal's photography honed by Natalie Kalmus's color direction brought out the best in Vincent Korda's production design. The many, many matte artists who went to work on this film really did a hell of a job. The blues in particular are tremendous.

Directed in part by (small wonder) Michael Powell, master of outlandish colour schemes and pointy facial features, this film is one cinema's great fairy tales (from a time when they could still be done innocently and beautifully a la La Belle et la Bete and les Enfants du Paradis). George Perinal's photography honed by Natalie Kalmus's color direction brought out the best in Vincent Korda's production design. The many, many matte artists who went to work on this film really did a hell of a job. The blues in particular are tremendous.

The Best Cinematographic Achievements in Film, dated 9/5/08

A while back I began noticing that I stopped viewing the natural world around me as I once did. I started looking at things, really looking at things - trees, ditches, fields, snow-covered flora - and began imagining them in different ways. Slowly my appreciation became deeper, in a twister sort of way it's no longer a simple matter of "this is nice looking", it's now "this is beautiful, it would look gorgeous on film. How might I film this?" An occupational hazard, I suppose. I'm not really a cinematographer - technically speaking of the three short films I've taken part in in the last year, I only photographed two of them, and only one of them I can say I really had a sense of what I was filming - it's more the sense I've been given since giving myself an education in cinematography slightly more in depth than the one I've been given twice in two different schools. I like my own self-imposed knowledge better because it meant watching all the movies that get roped in together as the best. I'm not saying that these estimations are incorrect, I just happen to think looking beyond the same five films in every summation is always a good idea. For example, in looking at the humbling work of master photographer Nestor Almendros, the film he gets most credit for is undoubtedly Days of Heaven. While I agree that the work is unrivaled in it's technique, I think more can be gained watching his first feature film La Collectioneusse, a film done without a single electrician or industrial light. I think the greatest feature of cinematography is that a film needn't be good to have rich photography. For example I greatly admire Roger Deakins work (on every one of his films, but especially) on The Village and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, two films greatly wanting in other areas. I will say that I have favorites, those who have honed their craft into the purest of art forms, but the other redeeming feature of the field is that a novice can do just as beautiful work as a seasoned professional. Look at Mihai Malaimare Jr., who cut his teeth on three short films in his native Romania before taking on the dubious Youth Without Youth, a film that couldn't look more beautiful if the cast were all greek nudes. I think it's probably all the more impressive when Cinematographers can make as splendid use of shadow in Black and White film as shades and hues in color film. The Third Man (nay, the whole Noir genre) would be nothing without the work of it's light and shadow men. Imagine Detour, M, The Lady From Shanghai, or Kiss Me Deadly without their notorious shadowplay. Cinematography is often responsible for a film's most striking aspects. Picture a less competent man than Frederick Elmes behind the lens of David Lynch's flooring Blue Velvet, or someone with less experience in the expressionist movement than wunderkind Fritz Arno Wagner filming the famous stair sequence in Nosferatu, or most terrifying, imagine if David Lean had hired anyone other than cinematographer Freddie Young when filming Lawrence of Arabia, someone who wouldn't have had the resources to get ahold of a 482mm lens to film Omar Sharif's awe-inspiring entrance. I shudder to think. Below are my fifty favorite instances of cinematography in feature length films and their accompanying cinematographers, or really what I think are the most technically accomplished/beautifully filmed movies of all time. I've given descriptions of the top ten, as reading descriptions of fifty films might get as repetitive as writing them. How many synonyms are there for gorgeous, anyway?

1. The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford – Roger Deakins

This film has something of a mixed reputation. I personally think it a bit heavy-handed and melodramatic at times and I think it could have done without the prosaic voice over narration, but one thing is absolutely without question: the movie is stunning to watch. Right from the start when we see the James Gang knocking over a train, while Brad Pitt strides past the steam of the locomotive, while the light from the passenger cars douses the bandits in gold, while the dark wood of the cars clashes with the shining metal of firearms, while the silhouettes of every member of the gang closes in on the brightly lit train cars. It's amazing and Roger Deakins made sure to fill every frame of the film with otherworldly beauty. While director Andrew Dominik's tribute to the westerns of Anthony Mann and Samuel Fuller lingers in the past, Deakins makes a showing for the age of technology. The leads in their eccentric costumes standing like pillars of marble in the blazing scenery Deakins photographs. The blue-hued snowy landscapes, the dusky fields and farms of James' hometown, the exquisite dinner scenes we're drawn into. The film's screenplay may lack subtlety, but Deakin's photography needs none.

2. The Double Life Of Veronique – Slawomir Idziak

3. La Collectioneusse – Nestor Almendros

Almendros will forever be immortalized as one of cinema's greatest eyes, but he'll rarely get the credit he deserves for his best work. His work with Barbet Schroeder and Eric Rohmer far outshines his work in America in almost every case. With the aforementioned exception of Days of Heaven, his best work was done in France. This film, his first, is the deceptively simple tale of one man's struggle to conquer his feelings for a promiscuous girl as she learns to settle down. I'm not the least bit ashamed to admit that I was a little too preoccupied with Almendros' camera work to pay close attention to the story (the ending's happy, if memory serves). At times Almendros had ony two pieces of equipment while working on La Collectioneusse, a 35mm camera and a particularly bright bedside light (the bulb was intentionally replaced with something industrial grade). The rest of the time he had natural light and reflective surfaces. Any given still from this movie could easily be mistaken for some lofty Renoir-esque painting. He'd may have gotten cleverer, but his work never got more flawless than it did on his first feature.

Almendros will forever be immortalized as one of cinema's greatest eyes, but he'll rarely get the credit he deserves for his best work. His work with Barbet Schroeder and Eric Rohmer far outshines his work in America in almost every case. With the aforementioned exception of Days of Heaven, his best work was done in France. This film, his first, is the deceptively simple tale of one man's struggle to conquer his feelings for a promiscuous girl as she learns to settle down. I'm not the least bit ashamed to admit that I was a little too preoccupied with Almendros' camera work to pay close attention to the story (the ending's happy, if memory serves). At times Almendros had ony two pieces of equipment while working on La Collectioneusse, a 35mm camera and a particularly bright bedside light (the bulb was intentionally replaced with something industrial grade). The rest of the time he had natural light and reflective surfaces. Any given still from this movie could easily be mistaken for some lofty Renoir-esque painting. He'd may have gotten cleverer, but his work never got more flawless than it did on his first feature.4. Children of Men – Emmanuel Lubezki

Ok, so it's no secret in the film world that this movie is brilliant. As my friend Lizzy said after her first viewing "I wasn't expecting much, but...". The movie really didn't scream "genius" when it made it's pitiful rounds of American multiplexes and so expectations were all but erased by the time it hit DVD, but it was cinephiles who had the last laugh. This movie is, and I don't mean to hyperbolize, the most technically exceptional movie ever made, where live film is concerned. Emmanuel Lubezki, hands down my favorite cinematographer, manages to revolutionize the real-time tracking shot while still doing wonders with he and director Alfonso Cuarón's trademark green hues. His active lens makes sick situations frighteningly real and all the more nauseating; his camera seems to trigger the release of endorphins, like a rollercoaster, because when the ending titles began flashing, I couldn't help but feel both mildly ill and like I needed to see it again; it was all I could talk about for days. Lubezki's greens are a favorite of mine (you'll notice his name five times more on the list) and they're subdued just enough here not to take center stage like they do in Cuarón's earlier work, but they still manage to catch the eye despite the chaos that consumes the frame. Lubezki and his crew should have been given nobel prizes for their work on this film; not just because they manage to stay on a battle for 6:18 without ever making it obvious that cuts are being snuck in, but for making the most horrific things in the world look so vivid and unforgettable. If viewers never forget what they see, they may just act accordingly later in life.

Ok, so it's no secret in the film world that this movie is brilliant. As my friend Lizzy said after her first viewing "I wasn't expecting much, but...". The movie really didn't scream "genius" when it made it's pitiful rounds of American multiplexes and so expectations were all but erased by the time it hit DVD, but it was cinephiles who had the last laugh. This movie is, and I don't mean to hyperbolize, the most technically exceptional movie ever made, where live film is concerned. Emmanuel Lubezki, hands down my favorite cinematographer, manages to revolutionize the real-time tracking shot while still doing wonders with he and director Alfonso Cuarón's trademark green hues. His active lens makes sick situations frighteningly real and all the more nauseating; his camera seems to trigger the release of endorphins, like a rollercoaster, because when the ending titles began flashing, I couldn't help but feel both mildly ill and like I needed to see it again; it was all I could talk about for days. Lubezki's greens are a favorite of mine (you'll notice his name five times more on the list) and they're subdued just enough here not to take center stage like they do in Cuarón's earlier work, but they still manage to catch the eye despite the chaos that consumes the frame. Lubezki and his crew should have been given nobel prizes for their work on this film; not just because they manage to stay on a battle for 6:18 without ever making it obvious that cuts are being snuck in, but for making the most horrific things in the world look so vivid and unforgettable. If viewers never forget what they see, they may just act accordingly later in life.5. Autumn Sonata – Sven Nykvist

I'd seen a few of Nykvist's collaborations with Ingmar Bergman before I saw Autumn Sonata, but I had no idea just how well the two men understood each other. I don't know that there's a team that had such insight into the world of the other anywhere else in the annals of film history. I suppose Greg Tolland and Orson Welles came close, as do Cuarón and Lubezki, but the difference between any other teaming and this one, Bergman's entire life came out of Nykvist's camera. So when Bergman makes a film with an Autumnal motif, Nykvist came through beautifully. The movie looks effectively like the fall has come to life in Liv Ullmann's house. The faded pastel colors and rich outdoor scenery are truly remarkable and as someone who admires Autumn more than any other season, this is a wonderful thing.

6. The New World – Emmanuel Lubezki

If you paused any given second of The New World and squinted, you'd think you were staring at an oil painting. Lubezki outdoes himself at his better-than-reality camera work, and easily steps into Nestor Almendros' shoes as the undisputed master of natural light photography. There's one scene in particular that comes to mind when I consider Lubezki's work in this movie; it's the last one in the film. Thanks to director Terrence Malick's set-up and romantic reverence for (almost deification of thanks to the camera work) of death, what we have is a scene that easily qualifies as transcendence, if we adhere to Paul Schraeder's definition. Lubezki manages to craft a convincing picture of heaven without ever leaving the realm of the living, which I call a job well done. He and Malick understand that death is not an end, so much as it is a celebration of the middle. With a good camera man, it's not hard to do so.

If you paused any given second of The New World and squinted, you'd think you were staring at an oil painting. Lubezki outdoes himself at his better-than-reality camera work, and easily steps into Nestor Almendros' shoes as the undisputed master of natural light photography. There's one scene in particular that comes to mind when I consider Lubezki's work in this movie; it's the last one in the film. Thanks to director Terrence Malick's set-up and romantic reverence for (almost deification of thanks to the camera work) of death, what we have is a scene that easily qualifies as transcendence, if we adhere to Paul Schraeder's definition. Lubezki manages to craft a convincing picture of heaven without ever leaving the realm of the living, which I call a job well done. He and Malick understand that death is not an end, so much as it is a celebration of the middle. With a good camera man, it's not hard to do so.7. Last Of The Mohicans – Dante Spinotti

This movie is probably responsible for my appreciation of nature. It's why while riding in trains or cars I'm constantly tempted to get out and become part of my surroundings. Michael Mann's tribute to the ways of the Native American (as some kind of bastard Native American myself, I get to relate on more than one level to this movie), namely their constant graciousness toward the kind earth they live on. All you really need to understand the genius of this movie and of Dante Spinotti's lens; Hawkeye, Uncas, and Chingachgook run through the woods chasing after a buck. Their surroundings whir past them, occasionally giving us glimpses of the deep greens, browns, and blues of the woods. Finally they settle on a good spot to take the animal down. In a clearing, with water running through a small brook, rich foliage both living and dying, the sun nearly down, providing minimal light. There they claim their prey and then they give thanks, while all around returns to it's usual stillness and the beauty of the natural world is restored. These men do not top the food chain, they are merely one rung; nor do they stand out against their background, they are merely one piece of a sensational picture.

8. Sweet Movie - Pierre Lhomme

This movie is little known in the United States outside of the ravenous cineastes who hunger for each new Criterion release. This, friends, is a damn shame. The movie, a madcap fusion of political theory and sexual politics in the extreme, is made all the more poignant because the beauty of its most puzzling and challenging images is identical to that of its most serene. Take for example that a scene of two people copulating in a vat of sugar is just as clear and breath-taking as that of a long shot of a boat made out trinkets and political artifacts with Karl Marx as the figurehead tooling down a crowded canal. The movie's incendiary nature wouldn't be half as effective without Pierre Lhomme's beautification of every dirty detail, and this movie gets pretty dirty.

9. I Fidanzati - Lamberto Caimi

Black and White photography is easy to make look good, easy to look sloppy and incoherent, and hard to make perfect. Would you believe that one of the most mesmerizing sequences in the history of black and white film was shot by a first-time cinematographer. I guess technically I Fidanzati was Lamberto Caimi's third film, but his work on his first movie, Il Posto, was essentially identical to his work here. Ermanno Olmi's films, which were Caimi's first gigs, evolved out of work-place documentaries their factory produced, which were amazingly well-realized and insightful. Even more impressive was that the photography was just as impressive as anything that showed up in any of Fellini's films of the same period. The sequence I described earlier takes place about midway through the film. The protagonist walks from a beach to a tired-looking derrick nearby. It looks like a precursor to the kind of work Robert Elswitt would do in There Will Be Blood. The textural capabilities of black and white film are as pronounced as I've ever seen them.

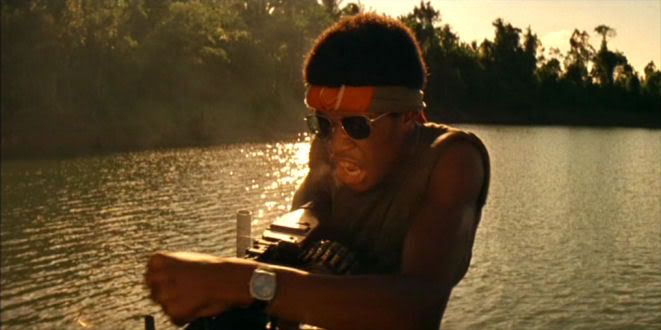

10. Apocalypse Now – Vittorio Storaro

I once tried to explain to someone why I loved cinematography so much, using Apocalypse Now as a sort of exhibit A (my actual wording was fairly juvenile, but it was only to get my point across). I've often thought of the film as DP Vittorio Storaro's as much as director Francis Ford Coppola's because he's half the reason this movie is so outstanding. When Martin Sheen reads over Kurtz' dossier while "Satisfaction" blares on Clean's radio, there's nothing better. The contrast between Sheen's tanned, hairy skin, and the crystal blue waters below him have long symbolized the genius of the film; light vs. dark, American men vs. the natural world. The point becomes clearer minutes later when Robert Duvall's Air Mobile unit shreds the bejesus out of VC target zone so that he can surf a six foot peak. The overwhelming violence stood out to my friend, which is of course the point of an anti-war film. Another viewing or a little more knowledge of cinematography and she'd see that the reason anti-war films of this caliber work is because, like Children of Men, the violence is shrouded in so glorious a light, because that's how it appears to the men who make war and because that is how a clear picture is crafted. How do you make someone remember your anti-war message? You give them images they'll never forget - they can be violent, they can be troubling, but they can also be beautiful.

11. A Very Long Engagement - Bruno Delbonnel

12. Master & Commander: The Far Side Of The World: Russel Boyd

13. Birth - Harris Savides

14. The Thin Red Line – John Toll

15. Maitresse – Nestor Almendros

16. Down by Law – Robby Müller

17. Au Revoir Les Enfants - Renato Berta

18. The Third Man - Robert Krasker

19. Gate Of Flesh - Shigeyoshi Mine

20. Broken Flowers – Frederick Elmes

21. The Village – Roger Deakins

22. Lawrence Of Arabia – Freddie Young

23. Y Tu Mama Tambien – Emmanuel Lubezki

24. The Straight Story – Freddie Francis

25. Manhattan - Gordon Willis

26. Days Of Heaven – Nestor Almendros

27. Great Expectations – Emmannuel Lubezki

28. The Conformist – Vittorio Storaro

29. Sleepy Hollow – Emmannuel Lubezki

30. Contempt – Raoul Coutard

31. Cries & Whispers – Sven Nykvist

32. George Washington – Tim Orr

33. Youth Without Youth - Mihai Malaimare Jr.

34. Fargo – Roger Deakins

35. Brief Encounter - Robert Krasker

36. Blowup - Carlo Di Palma

37. Pierrot Le Fou – Raoul Coutard

38. McCabe & Mrs. Miller – Vilmos Zgismond

39. Harry Potter & The Order Of The Phoenix – Slawomir Idziak

40. A Little Princess – Emmanuel Lubezki

41. Gosford Park – Andrew Dunn

42. There Will Be Blood – Robert Elswitt

43. Interiors - Gordon Willis

44. Port of Shadows - Eugen Schüfftan

45. Ivan's Childhood - Vadim Yusov

46. Let Sleeping Corpses Lie - Francisco Sempere

47. Blood For Dracula - Luigi Kuveiller

48. 28 Days Later – Anthony Dod Mantle

49. Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon – Peter Pau

50. The Mission - Chris Menges